As a dialectologist, Carlota de Benito Moreno is interested in how linguistic features change over time and space. By plotting her data on a map and combining it with historical data, she can detect diffusion patterns, divides, or clusters. Sometimes, she even discovers something she did not expect.

(for an explanation of the linguistic terms marked with an asterisk *, see the box at the end of the article)

Carlota started using a GIS software already during her Master’s in dialectology at the Autonomous University of Madrid. “It was a bit hard for me in the beginning”, she says, “As I was not used to storing my data in tables.” But tables were needed to import the data into the GIS software and then further analyse and display it on a map. The first time she saw her data mapped, she thought: Wow, it’s amazing! “However, this happens every time”, she admits, “I really love to see my data displayed on a map.” Throughout her PhD thesis, she continued working with a GIS and tried out different software from ArcMap to QGIS.

“When I arrived at UZH, I participated at a workshop organised by the University Research Priority Program Language and Space (URPP SPUR) and got connected to the geographers who also supported me later on whenever I had a question”, Carlota says. She continues: “Now that I am used to different GIS software, I found them easy to work with.” She even produces tutorials to help other linguists to plot their data on a map. In the meantime, Carlota switched from a GIS software to R, a statistical software, to analyse the data, but also to map it. “I think R comes in handier if you change something in your data and you just want to redo the map and export it as a picture. In R, I just rerun the code while in a GIS software, importing the data again and exporting the map as an image seems more tedious to me”, she argues.

21 dog or 21 dogs?

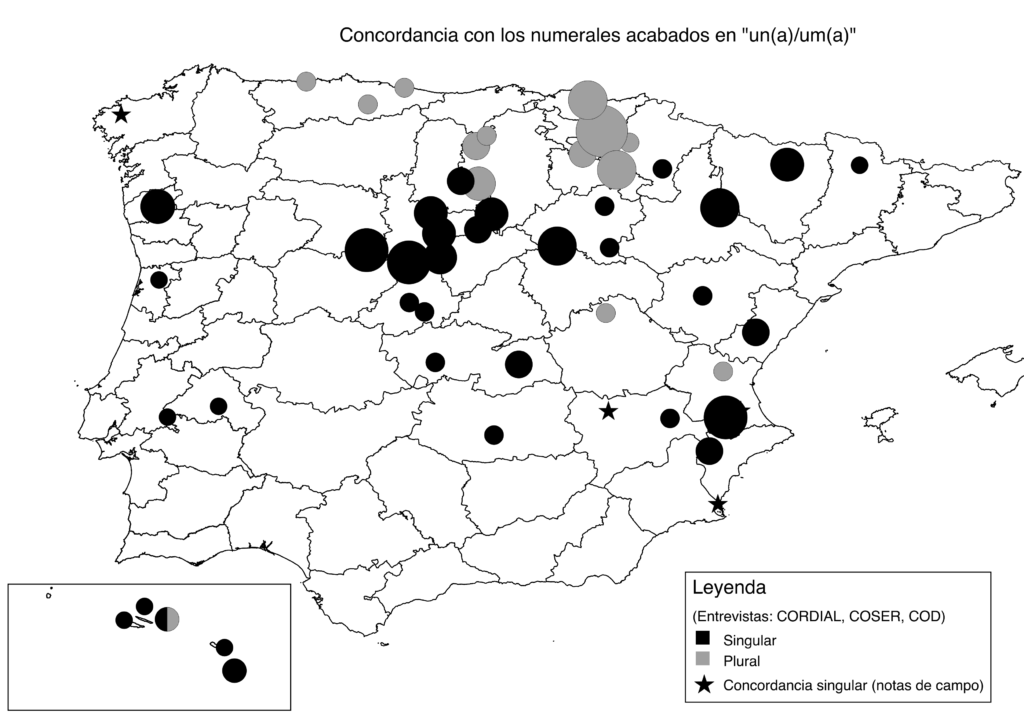

In one of her projects, Carlota is interested in rural features that are present in dialects all over the Iberian Peninsula, even though they are not part of the standard language. She argues: “To discover that such substandard features exist was something I did not expect as these features defy the prevailing idea that the standard is the language that has spread across the entire country and has erased the dialects.” An example of such a substandard feature is that in rural areas people say ‘ventiún perro’, which means ‘twenty-one dog’. “The peculiarity is the noun in the singular form as the number ends on one, regardless of the two tens”, Carlota explains. The standard agreement would be the plural form ‘ventiún perros’ (‘twenty-one dogs’ in English). Carlota looked at four such substandard features and analysed how they are spatially distributed and how they evolved in the historical context. “By combining the maps with historical data, I made a proposal why we could have those spatial patterns”, she says. Carlota came up with three reasons: “One reason is that these features are polygenetic. This means that they did not diffuse, but just appeared everywhere – a bit like mushrooms – as they happen easily.” Another reason according to Carlota is that these features are very old. They were present all along in the rural areas, but never made it to the region’s standard language. “The ’21 dog’ example i.e., even appears in Portuguese and Catalan. It is already there in the 13th century, the beginning of our documentation, and somehow made it to the 21st century”, she says laughing.

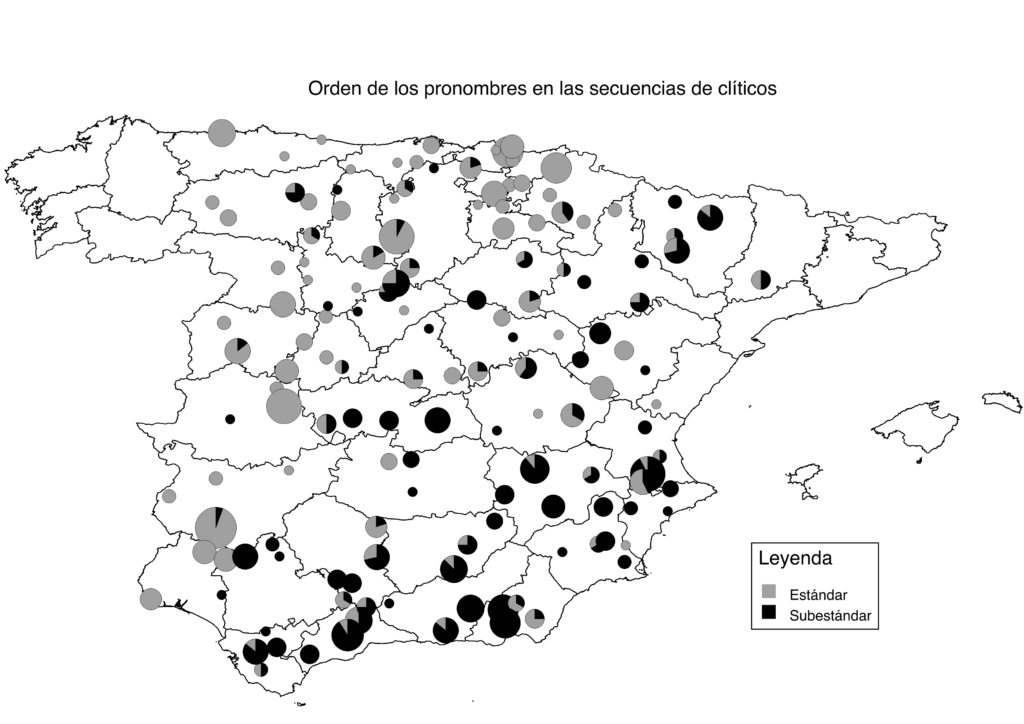

“The third reason is that they have been diffusing across the whole territory without being standard”, she explains. A feature for the latter reason is the order of pronouns in reflexive verbs. Carlota explains: “The standard agreement is ‘se me cayó’ (‘I dropped it’ in English), where the reflexive pronoun comes first, as opposed to the substandard version ‘me se cayó’.” By combining the map with historical records Carlota concludes that “this feature is also widespread, but more dominant in the west. It first appeared in the 15th century and is younger than the ’21 dog’ example. So, it must have been diffused from west to east without ever becoming standard.”

Patterns on the Canary Islands

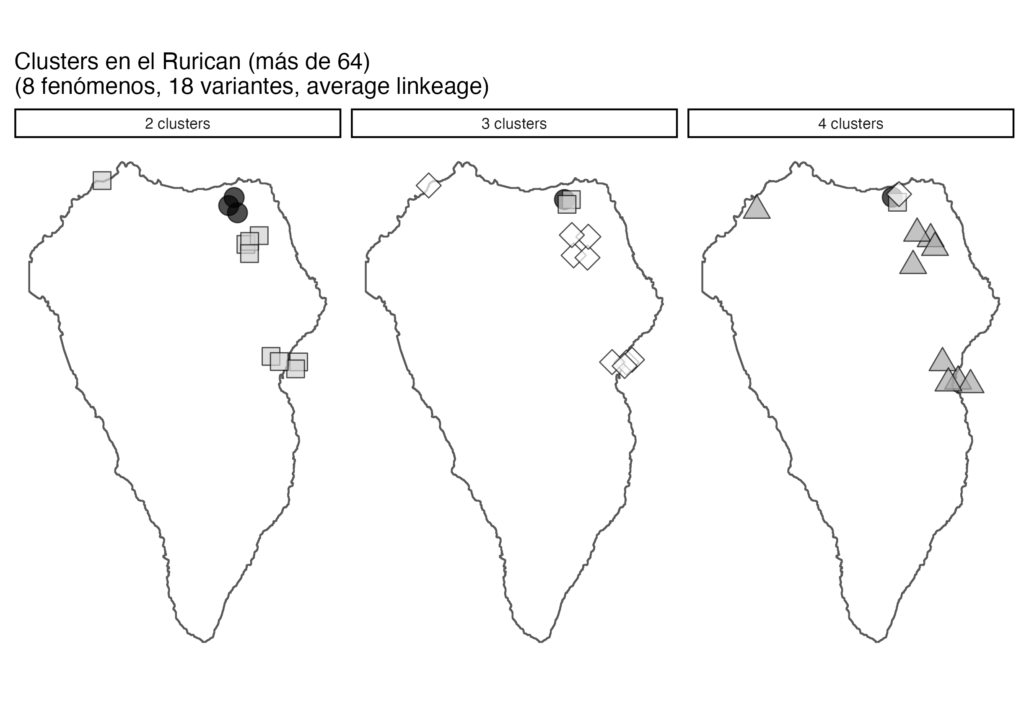

In a current project, Carlota together with other researchers studies the speech in two Canary Islands. The project is called RurICan which stands for ‘Rural sociolinguistics in the Canary Islands: linguistic innovation and diffusion’. “The Canary Islands are interesting as within a town, there can be a lot of internal variation nowadays. And from a historical perspective, the Spanish on the Canary Islands does not have the same spatial diffusion pattern as in Spain”, Carlota explains. She proceeds: “When the Arabs arrived in the Middle Ages, all Roman languages were erased from most of the Iberian Peninsula. Later, the Christian kingdoms reconquered the territory and spread their languages from north to south. This is why we often have a north-south pattern for linguistic features on the peninsula.” However, on the Canary Islands, there is no such pattern, she explains: “We find smaller dialectal areas on the Islands which are due to different reasons that we still do not know as the spatial distribution there is not well studied.” This is where Carlota’s research comes in: “We want to find out if these features pattern geographically, socially or both.” Together with two Post Docs, she interviewed around 200 people, 20-30 people in four towns on the two islands La Palma and La Gomera. The interviewees are of different gender, age, and background. To find out what linguistic features these people use, they were asked several questions about their life, their profession, how they grew up, etc. The interviews were annotated for different linguistic features and each person was assigned a linguistic profile. The features were then mapped to calculate clusters. Carlota explains: “We want to find out who groups with whom and how linguistic features travel around the community as we know that some features are dialectally very marked*.” Carlota assumes that people get rid of or lose some of the features once they enter school or leave the islands to study or work abroad. The results are not conclusive yet, Carlota says: “So far, we have only analysed a small sample in the north of La Palma.” Due to the volcano eruption on the island in 2021 and the pandemic, they had to change the towns as well as the timeframe of the fieldwork. “In the end, we will compare the clusters to other sources like a linguistic atlas from the 1970s and a corpus with data from elderly people”, she explains.

Spatial pattern of social network data

The sources she uses are very varied. Carlota gives an example: “I also work with data from social networks like Twitter. There are features from colloquial speech that seem to have either appeared or diffused through social networks. Due to this diffusion, I expect a completely different spatial pattern with more contacts between countries.” Another kind of data is substandard features that are known to be geographically restricted. “We try to find out if we can reproduce this spatial pattern in Twitter”, Carlota says, and adds, “But this is more of a methodological research.” However, one has to be careful with Twitter data, she objects: “In Twitter, there is no control over the participants. We do not know if the location in the profile is the place where someone lives, is from, or maybe the place of his or her dreams.” The more people move, the harder it is to assign a location to them and use the data for scientific research. “In Twitter, it is a bit like in the wild wild west”, Carlota observes and laughs.

In her future research, Carlota will continue working with maps. “As a dialectologist, I am always interested in geographical patterns. And a map is a fast way to explore my data and gain more insight”, she says. “Even if there is no pattern, it is interesting. It means that I have to look into it in more detail”, she is convinced.

Carlota de Benito Moreno is an Assistant Professor of Language and Space in Ibero-Romance at the Institute of Romance Studies at UZH. In her linguistic research, she focuses on dialectology. She deals with language variation and change over time and space, in Spanish and other languages. To collect data, she interviews people, but she also uses existing data coming from linguistic atlases or Twitter.

*Linguistic terms explained

Dialectology is the study of regional variations of a language i.e., how variants are spatially and socially distributed. The variations can concern the use of different words for the same object, a different pronunciation of a word, a different syntax etc. (Richards and Schmidt, 2010).

Standard language (also standard variety, standard dialect, standard) designates the variety of a language “[…] with the highest status in a community or nation” (Richards and Schmidt, 2010: 554). The standard language usually corresponds to the language used in the news media and literature, it is described in dictionaries and grammar, and it is taught to non-native speakers as a foreign language (ibid.).

Reference

Richards, Jack Croft; Schmidt, Richard W. (2010). Longman Dictionary of Language Teaching and Applied Linguistics. Pearson Education Limited. ISBN 978-1-4082-0460-3.